Blame Your Laziness on Hyperbolic Discounting!

- Chetan Reddy Madadi

- Feb 19, 2021

- 6 min read

Generally, most humans are inherently impulsive and weak-willed. For example, instead of starting on our assignment, we might decide to watch an extra episode of our favourite show. This eventually turns into a whole season (or more) in one sitting. We naturally seem to prefer postponing tasks for the future, rather than completing them immediately. This habit of putting things off repeatedly is known as procrastination, and is fairly widespread among university students. The readers of this article are no exception - midsem/compre is starting soon, guys. What are you doing scrolling through FB?

Now, while we may be masters at delaying certain matters, we just can't hold out on others. We compulsively do several things such as overeating, drinking too much, and indulging in several other behaviours that only lead to regret. Why do we indulge in these activities that satisfy us for now (temporarily) but lead to regrets in the long term? Do we, the people facing these problems, not wish to maximize our happiness? In this article, we are going to explore these "self-control" problems from the perspective of economics.

Both these failures in self-control discussed above seem to act in opposite directions - one makes us delay what we are supposed to do while the other doesn't let us delay what we should not do. However, they emerge from the same problem: while evaluating the costs and benefits of an action(or inaction), we tend to put too much weight on the here and now. Behavioural economists refer to such misguided decisions as "time-inconsistent preferences." Time-inconsistent decision-makers are commonly described as having "different selves" at different points in time that make inconsistent choices with each other. As an example, consider the following questions:

● Would you prefer to be given 500 dollars today or 505 dollars tomorrow?

● Would you prefer to be given 500 dollars 365 days from now or 505 dollars 366 days from now?

To be time-consistent, we have to choose the same option for both questions(either 500 or 505.) This is because we get the same extra 5 dollars for both the questions if we wait for one more day. The only difference in both these questions is that they refer to different points of time(a- present, b- one year from now) However, people are not always time-consistent. People tend to choose "500 dollars today"(from question a) and "505 dollars 366 days later"(from question b).

To be sure, time-inconsistency arises in several settings, and procrastination is only one of them. Similarly, theoretical explanations for this phenomenon abound, but we stick to the one that is commonly used and easiest to understand.

A Mathematical Model of Time-Inconsistent Preferences

In a classic exponential discounting model, the present utility(utility to our present self) of a future expected utility decreases smoothly as the utility realization period increases. This indicates time-consistent preferences.

In this model, the present value of one's utility from consumption(or certain activity) over the next T periods can be written as: Where δ is a constant discount factor{δ = 1/(1+r)} In the equation, δ^n u(xn) refers to the utility that we receive from our activity at a time-period n discounted to present time.

Since time consistency is not a reality here, we need a different/more accurate model. Therefore, we use the beta-delta discounting model(a superset of the exponential discounting model) which has a property of time inconsistency. In this model, the present value of one's utility from consumption over the next T periods can be written as:

While other things are the same as the exponential discounting, we have an additional parameter β here. β is the present bias parameter, as it measures the extent to which future outcomes are weighed relative to the current one.

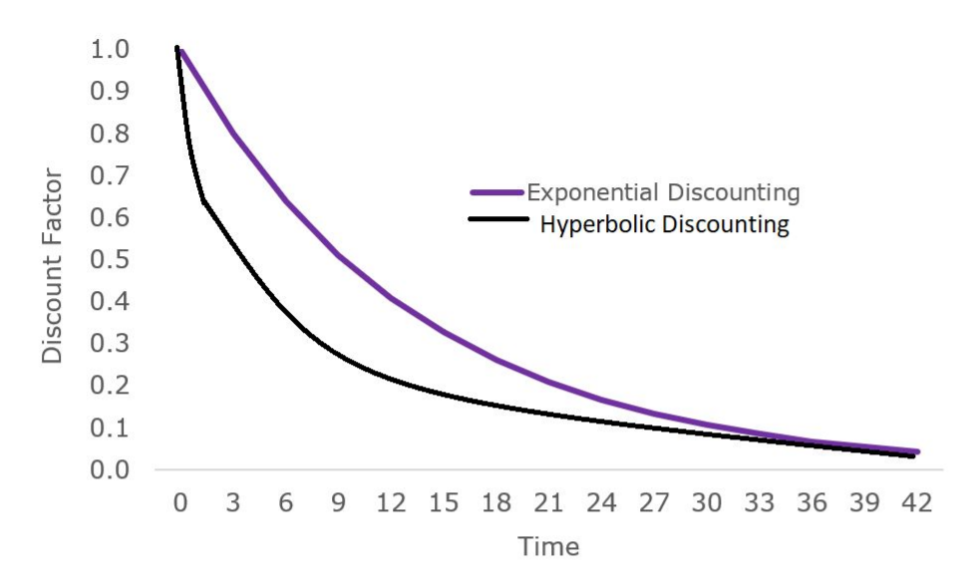

To see how this changes anything, we need to how a certain utility we perceive in the present changes with change in how far in the future we receive this utility. In fact, let’s graph this and compare both models. In the below graph, the discount factor refers to δn or β(δn) for the exponential and hyperbolic models respectively. The lesser the discount factor, the lesser is the utility we perceive at the moment(at present).

As we can see, there is a sudden dip at the start of the graph for hyperbolic discounting. This sudden dip is due to the presence of β. It is a dip in the utility we perceive in the present with respect to how far in the future we receive this utility(say year 1). Due to the sudden dip, for situations in which we pay a lot now(things with negative utility like working hard or saving up from our salaries) and enjoy the continued benefits later, it seems to make a lot of sense for us to hold off the painful experiences till year 1. At that point, a negative utility(cost of us working hard now) is discounted while a positive utility(enjoying the present time) is not. We always think- the time right now is precious- let’s wait till year 1 when the painful experience(of working hard) gets easier.

However, this is where we trick ourselves. If we wait till year 1 to do our work, the discounting graph just translates and our year-1 self becomes our present and we once again encounter the same optimization problem. This once again concludes with the same solution- let’s hold off till the next year to put in the work for something. Thus, we procrastinate. This continues till the cost of holding things off for the future becomes too high. At this point, we are already very late and we just have enough time to do subpar work.

Less Maths, More Explanation

As a result, we(our current self) will care too much about ourselves (present self) and not enough about our future selves. The self-control literature relies heavily on this type of time inconsistency. It relates to various topics, including procrastination, addiction, efforts at weight loss, and saving for retirement. "You have to complete your syllabus for an exam tomorrow morning, but just as you are about to start studying, you decide to watch just one more episode of friends." "You want to maintain a strict diet but just can't help yourself." Both of these bad decisions are the result of privileging the present you over you of tomorrow morning(future). This is because we view our future self as different from us.

We expect ourselves to have an ideal behavior in this non-existent future. With us privileging the present happiness, the marginal cost of doing the difficult(but rewarding) tasks right now exceeds the marginal benefits of doing it. Therefore, we end up postponing the date for doing our work again and again. All the while, we know in some corner of our brain that we might not stop this vicious cycle.

The Way Forward

From what we have seen so far, our problem is that we keep stowing away all difficult tasks to the future and living on the pleasures of the present. This is due to the way that we discount the utilities of the future. All we need to do is to ensure that the marginal cost becomes lesser than the marginal benefit of doing the task. To do this, we can decrease the effect of discounting which we put on future expected utilities. That is, make these future blurry details more clear in the present.

One way to bring the ultimate fruits of your long-term efforts forward to the here and now is by visualizing the sense of relief, happiness, and satisfaction that will ultimately come from a job well done (a pat on the back from the boss, perhaps coupled with fantasies of the promotion and pay raise that will surely follow). For some people, taking the opposite approach works better: visualizing the dire consequences of continued delay—a reprimand from the boss and the specter of a pink slip. Magnifying the costs of delayed action is a tactic often employed by public-health officials trying to get people to resist behaviours with short-term allure and long-term danger. For smokers looking for motivation to finally quit, a series of ads may provide some inspiration. This is also why we see Mukesh so many times.

PS - Best of luck with your exams and hopefully, you can finally get back to your studies :)

-By Chetan Reddy Madadi

Comments