Economics of Dating

- Anuradha Pandey

- Nov 30, 2021

- 8 min read

Disclaimer - Dating choices can be subjective

Dating is a hot topic these days. The urge and desire for human companionship and a significant other has increased after the pandemic. “Personality vs looks”, “the number of women are so less on Tinder”, “Trade Off of swiping left and right” are the most common phrases heard under the hood of dating. But, what is dating?

Wikipedia defines dating as follows: Dating is a stage of romantic relationships in humans whereby two people meet socially with the aim of each assessing the other’s suitability as a prospective partner in an intimate relationship or marriage.

Before this article seems to remind you of your “love” life, let me ask you - why look at dating from an economics lens? What has economics got to do with it? Dating can be seen as a “market”. For a non-economist, this might seem strange, “why a market? No one is selling anything right?”

The dating pool can be analyzed as a market where the supply and demand operate between two parties. Economics is the optimization of one’s choices under constraints. Economic principles can be applied to dating since it entails limitations and scarcity.

Merging the two terms together would form dating economics, which is the study of the dating market and the study of choices involved in the same.

This article tries to analyse dating economics and the decision-making process behind it.

Decision making before the dating period begins -

Every decision we make has certain constraints involved. One of the biggest universal constraints under which every individual operates is time. Under the limited amount of time, we have every day, we make certain choices, and let go of the others. The economist’s term for the “cost of letting go” is opportunity cost.

In general, we try to maximise the amount of pleasure we’d get in every decision. In economics, the measure for this “pleasure” is utility. In dating economics, we consider that dating yields pleasure for both the parties involved. McAdams, in his paper - “Intimacy: The need to be close” stresses that intimacy and affiliation motivates living. The need for affiliation is the starting point of attraction between individuals and individuals are drawn to each other to find an optimal balance of their need for affiliation.

The Approach Model

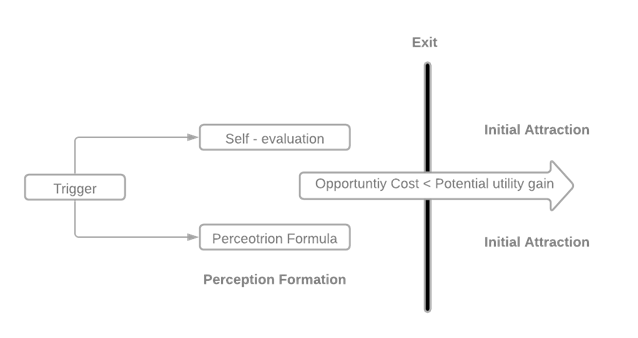

When a person first comes across someone, two evaluations determine whether they’re attracted to the other person or not, namely: self-evaluation and the first impressions of the other person. A higher evaluation of oneself will increase the likelihood of approach. The sum total of self-beliefs, self-esteem and self-perception impacts the decisions one makes in a social environment. The second evaluation which leads to formation of a perception is done on the basis of first impressions of the other person. The better the first impression of the other person is, higher are the chances of them being approached.

When the person fits in the perception formation and self-evaluation process, the next decision in line is whether to approach the person or not. Before making a decision, the potential utility gained/opportunity costs is assessed subconsciously. The amount of happiness a person can get from an interaction is referred to as potential utility earned. In this context, opportunity cost refers to the opportunities lost when meeting someone i.e. the possibility of meeting someone more or similarly appealing in future encounters. People will base their decisions on the perceived amount of potential utility gained from an interaction versus not being in that interaction.

The basic idea is to maximize profit and minimise losses.

Let CL = comparison level

People can have high CL or low CL where a person with high CL expects to be in a rewarding relationship and a low CL person does not expect as much from that relationship. CL is the minimum threshold required for a relationship to continue.

Let CLalt = comparison level for alternatives

CLalt denotes people’s expectations of what they’d get in alternate situations. A person with high CLalt would have more choices and be more likely to leave a relationship if the relationship nears the CL. People with low CLalt would be more likely to stay in a relationship even when the relationship nears the CL.

Hence, the equation can be summarized as - Rewards - Cost - CL = Satisf

action

Satisfaction - CLalt + Investment = Commitment

Till now we have discussed the approach model wherein we look for certain characteristics based on our self-understanding to determine our attraction towards the other person. However, apart from first impressions, there are attributes that influence attractiveness.

Two effects that influence attraction are the proximity effect and the exposure effect. Proximity refers to the physical proximity between the two people. The initial attraction is more likely to happen when both the people are at the same time and place. Exposure effect is the phenomenon of increased exposure to a positive stimulus, which is likely to result in higher attraction. The proximity and exposure effect may or may not have an impact on the interaction, but they only have a beneficial impact on a portion of the perception creation process and the initial encounter. Once perception creation has reached a certain level, the proximity impact and simple exposure effect will have little effect on the final decision.

Attitude similarity is another important factor in determining attraction. Interaction between the two people is a two stage process (Donn Byrne’s). The first screen is the dissimilarity negative screen. According to the approach model, people avoid associating with others who are not similar to them. The second screen is the positive screen of similarity, in which people are attracted to others who are extremely similar while being indifferent to those who are not.

After the perception is formed, this sense of value can be condensed into a single unit of value. For example we can say that an option on the dating market can be evaluated and assigned some number of “dating points” according to various attributes this option possesses. However, there are factors which influence the weightage of these dating points. At any given stage before dating, people are under participation constraint. A person's prior commitments and priorities decide the weightage of these “dating points”.

Consider two economic terms related to product differentiation, that we’ll use to understand the weightages - “vertical differentiation” and “horizontal differentiation”.

Consider purchasing a car after examining it. A car has many distinct qualities, such as speed, acceleration, horsepower, environmental effect, reliability, car style, car colour, and so on. In general, everyone agrees that higher ratings for speed, acceleration, and reliability are preferable than lower ratings for speed, acceleration, and reliability.

Similarly, everyone will agree that having a minimal environmental effect is preferable to having a big environmental impact. However, not everyone would agree that one automobile colour is superior to another (is black clearly superior to blue? ), or that one car type is superior to another (is the design of a Toyota Corolla superior to the design of a Honda Civic?). The qualities on which everyone can agree — speed, acceleration, reliability, environmental impact — are classified as vertically differentiated, i.e. everyone at a market level can agree these are desirable qualities and in which direction (lower or higher), whereas the qualities on which people cannot agree — colour, car design — are described as horizontally differentiated. These two words reflect market behaviour but not the size of individual preferences for these qualities.

For example, someone may be prepared to sacrifice a certain level of horsepower in exchange for a reduced environmental effect, but everyone would agree that both are desirable.

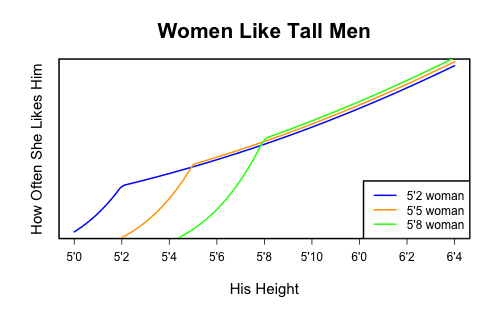

Source:

Similarly, in a dating market, attributes are vertically and horizontally differentiated. All choosers will likely agree on certain attributes, such as social intelligence, which are vertically differentiated. Whereas social status and physical attributes are subjective to taste of choosers, and are horizontally differentiated.

The Approach Model (contd.)

For any chooser evaluating any option i, the chooser is evaluating the option along two criteria, a value for the vertically differentiated attributes, vᵢ, and a value for the horizontally differentiated attributes, hᵢ, and the number of dating points the chooser assigns to option i is given by vᵢ + hᵢ. A chooser can then do this for any set of presented options and generate a preference list among that set.

From our set of all preference lists with corresponding vᵢ’s, we can calculate the marginal increase in dating points for all the vertically differentiated attributes. So at a market level, any option i can be assigned a value, vᵢ*, that corresponds to his market level vertical value as the sum of all the individual values of all his vertically differentiated attributes.

To bring the model closer to reality, we impose two restrictions - there are screening costs involved whenever a chooser evaluates the potential options, and there are finite resources available for screening.

Intuitively, it can be generalized that vertically differentiated goods tend to be easy to observe, things like height, income, age, etc, while horizontally differentiated goods are difficult to observe. Since the horizontally differentiated goods depend on the chooser, ultimately they’d have to meet the options to judge whether there’s “chemistry” between them. Moreover, given that we don’t have infinite amounts of money or time (due to finite lifespan), we also have a finite amount of resources with which to spend on screening. So choosers primarily evaluate options given easily observable vertical qualities. The strategy we use to analyse the combined effect of horizontally and vertically differentiated attributes is “assortative matching”. This means that we match the pair that is market rank #1, the pair that is market rank #2, etc, until we get to the pair that is market rank #n. Choosers evaluate their options and approach their highest preference. Since the market values are developed by the preferences of these choosers, most choosers should agree on who the highest valued options are and approach this subset of the options.

To understand assortative matching, consider the following scenario of 100 person micro-markets. The #40 chooses the #5 based on the initial self evaluation, attractiveness and vertical attributes. The #5 does not know the horizontal value of #40 and it has two possible responses - accept and reject. If the #5 rank option accepts, they have to incur the screening cost and reduce the total number of potential screens they can do since they have finite resources, and the best outcome the option can hope for is that #40 rank chooser has an incredibly high horizontal value, which will be difficult to know since it is not clear how to assess horizontal values.

From the option’s perspective, the horizontal values may well be random. If the option rejects, then the option has, in effect, maintained the opportunity to screen another higher ranked chooser’s proposal and this is likely preferable given that accepting the proposal of a higher ranked chooser will guarantee a higher vertical value, thus making the value floor higher, i.e. the high vertical value will ensure that the overall value of the chooser is at least somewhat high.

Considering these assumptions of vertical and horizontal differentiation, screening costs and budgets, it is clear that the proposal is usually accepted when there are similar vertical values. Since this behavior is symmetric when we flip the choosing and option groups, what we find is that people match at similar vertical values, i.e. assortative matching!

The article started by listing the different social psychological factors that come into picture which impact the initial attraction. However, as we proceeded with the model, there was more economics involved. The difference between social psychology and economics is that social psychology is often confined to single hypotheses and isolated modules. Using economics as the subject, we have tried to connect the dots and evaluate more options in the same context. We have used concepts of potential utility, CL, CLalt to base our hypothesis of maximising profit and minimising losses. The model was built using vertically and horizontally differentiated dating points, using assortative matching.

Different screening costs are involved, and the end decision made is restricted by the constraint of finite time and resources. Due to the increased visibility of the vertical differentiation, we concluded the proposals made are usually decided on the basis of vertical differentiation over horizontal differentiation.

The model presented in this article makes a lot of assumptions, and it’s not perfect or complete. It can be considered an early iteration of a hypothesis around how the dating market works with need for testing. This model can be useful in making optimum dating decisions, how people might do better at their searching for a partner, and how economists and technology firms might think about how to make digital matching platforms more efficient.

- Anuradha Pandey

Comments