Environmental Economics and the Tough Questions on Climate Change

- Economics Association Hyderabad Campus

- Jan 17, 2021

- 4 min read

A long-standing question in economics concerns whether human beings can grow and become richer without harming the environment. Are pollution, the greenhouse effect, and smog the by-products of economic development, or are they deterrents to growth itself? While these questions are valid for all countries, they are especially acute for India, which needs to feed more than 1.4 billion people and houses almost half the world’s malnourished children. For India, economic growth and prosperity is the only way to escape mass hunger, conflict, civil strife, and safeguard a generation of ambitions.

On the other hand, climate change and its several manifestations are a reality. Increasing temperatures do have negative consequences for economies - it lowers the agricultural yield, reduces labor productivity, leads to costly natural disasters (in 2020 alone, India was faced with 2 Billion-Dollar disasters), denudes the beaches kills tourism, and even causes child deaths. By some estimates, the cost of doing nothing - taking no action on climate change - is over 10 trillion dollars by 2050. For perspective, that’s more than three times the GDP of India.

Given such doomsday scenarios on all sides, the country leaders and bureaucrats are often trying to estimate the costs and benefits from climate change regulation. They want to find the right balance between doing something and not wholly jeopardizing economic growth, and they also wish to identify the right processes to achieve the famed sustainable growth. It is here that an environmental economist steps in - they provide the numbers and models that run the economy-development balance.

Here are just a few examples of the kind of work that environmental economists do:

As I mentioned earlier, there seems to be a tug-of-war between an increase in an individual’s income and a decrease in environmental quality. However, as Mark Rosenzweig and Andrew Foster show, this relationship might be far from reality. The relationship likely has an inverted U-shape - with environmental quality falling in initial days of economic development and then rising after that. As people become wealthier, they start putting a monetary value on the environment that surrounds them. For example, when we look for a new house to buy, we are ready to pay more for a home located in a pleasant-looking locality near a park instead of a secluded place in some dilapidated area. India has seen a similar forest transition - our area under forest cover reached its trough in the late 1970s and rose steadily through the 1980s and 1990s. This U-shaped curve is popularly called the ENVIRONMENTAL KUZNET’S CURVE and gives some hope for escaping the worst of environmental damage. But research on this issue is far from complete - we still do not fully understand how this curve arises and why it is found in some places and not in others. The figure above (from their work) shows a similar transition in the US.

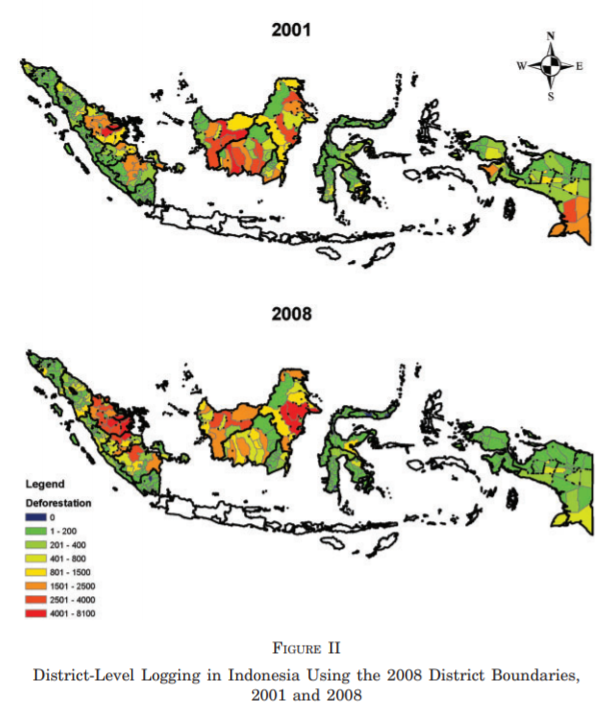

Another study on the determinants of deforestation in developing countries comes from Indonesia. Here, the authors try to understand the effects of creating new districts on deforestation. The logic was - since the district officers controlled the sale of Timberwood, having fewer districts means having lower competition among the sellers. This means that the price of wood would be high, and since many people would not afford it, fewer trees would be cut. As the number of districts increase, the price would fall down and deforestation would sky-rocket. And lo-and-behold! That’s exactly what the study finds. Increasing the number of districts speeds up deforestation and leads to worse environmental outcomes in Indonesia.

The third story comes from the electricity market. As we are aware, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has led a long-term mission of electrifying the entire country, and already 100% of villages have received electricity (by receiving electricity, we mean that at least 10% of houses in the village have some electrical connection. So even at 100%, we are far from having electricity in every home). Where does this electricity come from? Well, in India, almost 54% of electricity comes from coal, whose burning produces ash, soot, SO2, and several other chemicals that are toxic to health. How toxic, exactly? Well, a recent study by Dean Spears (my personal hero) found that air pollution caused by coal plants killed one infant every 5 minutes in India in 2019. On average, air pollution reduces the lifespan of Indians by 4 years.

With the rapidly falling costs of solar energy, hence, it should be obvious that our desire to electrify the countryside should rely largely on renewable sources of energy. Alas, that is not the case. Even as recently as 2019, the Government of India has decided to invest more than half the budget of new electricity generation into building coal plants instead of solar fields. This is in contrast with the rest of the world, where 90% of new investments and even new electricity has come from renewable sources for three years in a row.

An environmental economist is often charged with understanding these trends. Alongside development, environmental economics is at the forefront of economic research, inviting some of the best minds from social sciences, computer sciences, physics, and other fields. Major researchers and stalwarts in the field include Marshall Burke, Charles Kolstad, William Nordhaus, Dean Spears, Melissa Dell, Benjamin Olken, to name a few. You should check out their amazing websites for fascinating research! Also, feel free to reach out to me for more questions.

Comments