Everybody is Selfish

- Sai Kumar

- Mar 13, 2017

- 4 min read

Updated: May 21, 2025

Reading the title, you must have thought, ‘Obviously, that must be a mistake!’, but let me assure you, it is not, and I shall in due course present a well-founded argument to that effect. But first before we move on, let’s see what the exact definition of selfishness is.

Alright. Now that we have the language sorted, let me present my argument. Like any other proof, I shall lay down a few assumptions. But as our argument revolves around human beings and since we cannot necessarily predict human behaviour, we shall use a similar sentient albeit imaginary species widely known to economists as Homo Economicus. H.E is essentially a human being, but with a more constrained behaviour. And here are H.E’s characteristics:

E are consistently rational. (Now you get why we needed a new species, right?)

E are narrowly self-interested agents pursuing ends in an optimal fashion.

Let us call our personal Homo Economicus ‘Hom-E’. Now Hom-E, being rational and self-interested, will always want to be happy (who doesn’t). But how can he be sure he is as happy as can be? If only there was a way to measure happiness! But we have the next best thing! We can say a Hom-E will be satisfied if he is using all the resources he owns optimally and to the maximum, and there is a way to measure this, and it is called utility. Utility is defined as the satisfaction one obtains from using certain resources to one’s benefit. It is not a real physical quantity and therefore cannot be measured, but it can be determined through examining preferences of Hom-E over multiple combinations and quantities of different goods.

But before we move on, there are two things that we must remember about utility; one is that Hom-E always has a preference of one item over another at all points of time. That is, he can always rank stuff he wants at all points of time in a deterministic manner. And that given the option, he will try to use up all available resources to reach the maximum level of utility. For example, take the case of shoe laces, Hom-E has a pair of shoes and therefore needs only a pair of laces, any more, he has no use for it, and any less, he has no use for the shoes, so working within the constraints of the system, Hom-E chooses his utility maximising option, which is making use of one pair of shoe laces only, this maximises his utility without any needless wastage (Hom-E is rational, remember?).

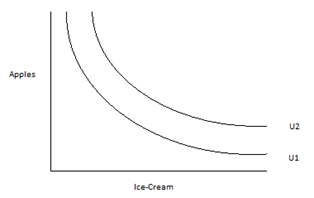

And now, a quick refresher on utility curves. Utility curves are always non-increasing. This is because the incremental happiness you get from having (or not having) more of a certain good decreases with the amount already in possession. E.g: To millionaires, a charge of Rs 750 (pun intended) might mean much less than what it does to people who are not as endowed.

Below, we can have shown two utility curves that could depict Hom-E’s preference for Ice-Cream and Apples. Each point on the curve represents a combination of goods that provide Hom-E with the same level of happiness. And also, happiness or Utility on curve U2 is greater than that on U1.

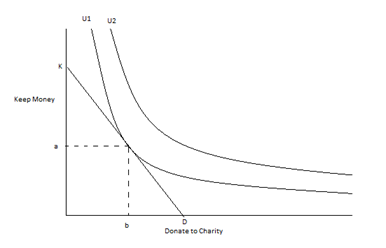

Coming back to our Hom-E, let us say he has some income ‘I’, and being the good and ‘charitable’ guy that he is, he has the option of keeping some money for himself or donating it. Keeping all the money for himself provides him with some utility but not as much as when he donates some and, in the same way, donating all his money gives him some utility, but not as much as keeping some for himself. Thus, the efficient point for him is somewhere in between. Consider the diagram below, the Y axis represents the amount of money Hom-E keeps and X-axis represents how much he donates.

Then, the total amount of money he can use is ‘I’, and suppose the amount of money he keeps is ‘k’ and the amount donated is ‘d’, then I = d + k and K = D = I, where ‘K’ is the maximum he can keep and ‘D’ is the maximum he can donate and also K=D as he can keep or donate only as much as he has.

If he were to donate ‘D’, then he would be on a lower utility curve as all utility curves are parallel to each other, thereby not in an optimal state of satisfaction. The case is the same at ‘K’.

Now, if he were to be in some intermediate state, he would be able to reach maximum utility, and that point is (a, b) where the Income line is tangent to the utility curve U1.

More formally,

I = d + k is called the budget line or the budget constraint. And suppose U = f(d,k) is the utility function, we want to maximise utility subject to the constraint I = d + k. This happens when their slopes match and the budget constraint is tangent to U. Slope of the budget constraint here is -1, and tangency occurs at point (a,b) (arbitrary).

Here, he donates ‘b’ to charity and keeps ‘a’ for himself and is therefore at the point where he is as happy as can be.

But by the conventional definition of selfishness, Hom-E is selfish only if he keeps all the money for himself, but from the utility curve, we see it is in Hom-E’s ‘narrow’ self-interest to donate ‘b’. Therefore, if we were to generalise and also relax the constraints on Hom-E, we can say that conventionally selfish people are selfish and conventionally philanthropic people are also inherently ‘selfish’. And thus, everybody is selfish.

Q.E.D

As a corollary, we can argue that Mother Teresa, who is often depicted as the epitome of benevolence was also selfish.

-Sai Kumar M

(Homo sapiens and Homo Economicus role-playing enthusiast)

Comments