The RBI’s Surplus Transfer Conundrum

- Siddharth Sampath

- Nov 2, 2019

- 9 min read

On the 26th of August 2019 the Reserve Bank of India issued a press release stating that it decided to transfer a sum of Rs.1,76,051 crore to the Government of India. This decision came considering recommendations from the Jalan Committee Report, which was constituted to review the existing Economic Capital Framework of the Central Bank. The committee, constituted on the 19th of November, 2018 had the task of analysing the extant status, need, and justifications for reserves and buffers presently provided for by the RBI, and check the practices followed by other central banks in assessing risks to the central bank balance sheet.

The call to transfer funds, however, was opposed by various parties, from the political opposition to a few high-ranking officials in the RBI itself, who raised concerns on the dangers of a breach of independence of the central bank. However, to fully understand this move, its implications, and the causes for concern, one must learn about the working of the RBI- namely its management of funds, its objectives, and the relationship it has with the Government of India. In this article, I intend to simplify the aforementioned aspects of the Central Bank and give both sides of the story of this controversial transfer of funds.

The RBI Balance Sheet

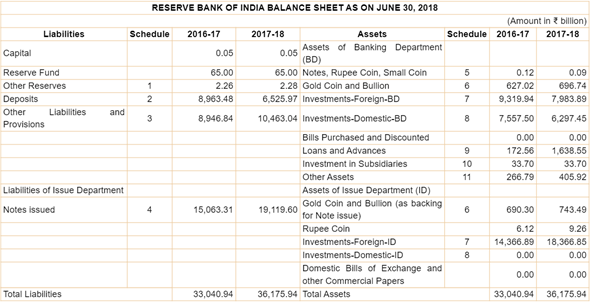

The RBI Balance Sheet essentially consists of two parts- Assets and Liabilities. The assets of the RBI include foreign and domestic investments, loans issued, a collection of gold coin and bullion among many other things. The Liabilities section, on the other hand, is comprised of deposits of various state governments, notes issued, the RBI’s capital, to name a few.

Although the Central Bank’s primary mandate is not to make profits, it does earn a lot of income through interest receipts from loans, dealing in the foreign exchange market, purchasing and selling bonds (in order to regulate the money supply), etc. After accounting for its annual expenditure, the RBI is left with a substantial amount of profit. It is the transfer of a share of these profits to the government that has been a bone of contention between a few stakeholders and the government. Before the Bimal Jalan Committee’s recommendations were adopted, the RBI would set aside a significant share of these profits into a Contingency Risk Buffer (CRB). The CRB is a fund used for securing the economy against undue stress, to maintain financial stability and monetary stability in case of a crisis. This is in line with the RBI’s main objective, i.e. Inflation Targeting.

Straying off topic for a bit here, it is interesting to known that while the choice of targeting inflation (keeping it constant at a particular level) has been made after considering the results of several research initiatives, the level of inflation was set to the low single digits (2 to 5 per cent) for three basic reasons, according to former RBI Governor Raghuram Rajan. The three reasons given by him were:

Even though the rich and well-off industrialists would benefit with a higher inflation because they would comparatively have to pay less in real terms on their debts, the average worker whose wage isn’t inflation indexed would be hit badly.

It has been found that higher levels of inflation are variable to a greater extent, which means the risk of breaching the threshold set is high. In simple terms, if the target level of inflation that shouldn’t be breached is closer to an inflation rate which has adverse consequences on growth, since the risk of the ceiling being breached is high, the probability of growth being affected negatively therefore, is high too.

A high level of inflation tends to feed on itself. In less complex terms, it means a price rise leads to an increase in wages, which leads to an increase in prices (too much money chasing too few goods), which in turn leads to an increase in wages and so on.

To sum this section up, the RBI’s cardinal duty is to maintain a stable price level (monetary stability) and to ensure the exchange rate doesn’t undergo unnatural fluctuations. In doing this job, the RBI tends to rake in huge profits, a significant share of which is going to be transferred to the government. In this context, it is useful to discuss the relation of the Central Bank with the Government of India.

RBI and the Government: A Contentious Relationship

The Reserve Bank of India draws its powers as India’s Central Bank from the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934. The RBI, as defined by the act, is essentially a banker to the Government of India, fully owned by it. In this context, it makes sense to argue that the profits earned by the bank belong to the central government. Moreover, Section 7 of the RBI Act specifically states that the Central Government can direct the bank to take a few steps in public interest.

“The Central Government may from time to time give such directions to the Bank as it may, after consultation with the Governor of the Bank, consider necessary in the public interest.”

Be that as it may, it is also of the essence that Central Bank of any nation enjoy a certain degree of independence. A simple explanation many economists give in support of the need for independence is that the political establishment would tend to keep short-term results in mind if it had the powers of the Central Bank. An independent Central Bank, on the other hand, would adopt policies that are formulated based on judgements made for the long-term stability of the economy. This being said, the present narrative is hinged upon the independence argument, with those against the move maintaining that the Government is encroaching upon RBI’s independence.

The RBI- Government ‘tussle’ seemed to reach its crescendo when Viral Acharya, the former deputy governor came lashing out at the government in October last year, saying: “Governments that do not respect central bank's independence will sooner or later incur the wrath of financial markets, ignite economic fire and come to rue the day they undermined an important regulatory institution.”

The Bimal Jalan Committee: Recommendations

Among the many suggestions given to the RBI by the Expert Committee to Review the Extant Economic Capital Framework of the Reserve Bank of India (or the Bimal Jalan Committee), one that’s raised eyebrows is the Surplus Distribution Policy.

According to the Committee, if the realized equity (a form of contingency fund for meeting risks and losses which is built up from retained earnings) is above its requirement, the entire net-income will be transferred to the government. However, should the realized equity be below the lower bound of requirement, provisions will be made as necessary, and the residual income will be transferred to the government. In its report, the expert panel recommends the RBI to maintain the CRB to the tune of 6.5%-5.5%, with 5.5%-4.5% being saved for monetary and fiscal stability, and 1% for operational risks.

With these recommendations from the expert committee, the RBI has decided to go for maintaining the CRB at 5.5% of the Balance Sheet and transfer the excess of Rs. 52,637 crores to the Government. This aside, the RBI also says: “While the revised framework technically would allow the RBI’s economic capital levels as on June 30, 2019 to lie within the range of 24.5 per cent to 20.0 per cent of balance sheet (depending on the level of realized equity maintained and availability of revaluation balances), the economic capital as on June 30, 2019 stood at 23.3 per cent of balance sheet. As financial resilience was within the desired range, the entire net income of ₹1,23,414 crore for the year 2018-19, of which an amount of ₹28,000 crore has already been paid as interim dividend, will be transferred to the Government of India. This is in addition to the ₹52,637 crore of excess risk provisions which has been written back and consequently will be transferred to the Government.”

The Transfer: Good or Bad?

This implementation of the revised Economic Capital Framework has left many policy analysts and economists divided, with some claiming this is the boost the economy needs in the current slowdown, and others saying the RBI’s independence is being compromised. Now that the entire situation has been explained, I plan to give both sides of the debate and let the reader decide.

To begin with, it is imperative for the reader to understand the effect of the numbers being thrown around in these discussions. Let’s consider GDP growth rate as an example. It has been observed that a 1% decrease in GDP growth generally leads to a 2% increase in the unemployment rate. With a country home to a gigantic population such as India, even 2% of the workforce adds up to huge numbers, if we were to assume an average of 3 or 4 dependants in the household on each job.

Now, there might be people wondering why politicians and economists aspire for an economy to have double digit growth rates (10% or more). A crude explanation for this is that economists agree a double-digit growth rate is instrumental in providing employment, because rates below that can be achieved by the existing workforce itself.

Arguments for the Transfer

Now, there is also the case to be made for the transfer of these funds. This is entirely based on the dire need for a fiscal stimulus from the government to stimulate the economy, increase demand for goods, and hence production. Another reason the government is adamant on receiving these funds, instead of resorting to borrowing, is because there is a fiscal deficit cap of 3.2%, which it intends to stick too. And even though people are saying that the it reflects a stubborn government; the fact remains that a fiscal deficit increase could be bad for an already slow economy. This can be understood by noting that, to begin with, all deficits need to be financed. To finance these deficits, governments need to issue bonds to the public, which in turn means investments elsewhere will reduce. In other words, an investor who buys T-Bills of Rs. 10,000 (say), is deferring a purchase of stocks worth Rs. 10,000 to buy these bills. Therefore, the capital available for investment into firms is bound to reduce. If this happens at a time when the RBI is on a rate-cutting spree (the Central Banks has decreased the interest rate by about 110 basis points in recent announcements), it would be serving no purpose.

There are high chances that the government will be using this windfall to recapitalize banks and give grants to sectors in trouble (the auto sector, for example). Considering the current state 0f the economy, this is a welcome sign as a capital influx in banks will lead to an ease in lending, and thereby creation of jobs. However, if the government were to use the funds for current expenditure, rather than for initiating structural changes, it would be a wasted opportunity for the economy as it had the chance to get back in shape by attacking the root problems that created this quagmire in the first place.

Another argument put forth for the transfer of funds is based on the relationship between the RBI and the government. This is where the RBI Act of 1934 comes in, which essentially says the government owns the central bank, implying any income earned by the RBI belongs to the Government of India. The reader should also note that the RBI, in principle, is an institution which was created to serve the people of India, and that it has a moral duty to aid the economy when in trouble.

Arguments against the Transfer

Those who are of the view that this transfer of funds is detrimental to the RBI, and the Indian economy differ on the reasons why this is bad for the economy. The main arguments on this side of the debate hinges on two main points- central bank independence, and the importance of buffer funds.

We’ll start by dealing with the latter. There is almost a universal consensus on the need for a country’s central bank maintaining a buffer fund for unforeseen circumstances. This aside, these uncertain times require any Central Bank to have a strong reserve of funds which safeguard the economy, while reinforcing investor confidence. This is the reason why critics remain apprehensive of stripping the RBI off such a huge volume of funds.

Those concerned about an adverse impact on Central Bank Independence also have a good case going for them. This is because it has been demonstrated, in the Indian context at least, that lack of political interference has resulted in a stronger, more decisive Central Bank (the RBI in the late 1990s, took major policy decisions when there was a weak government at the centre). Proponents of this argument also cite the resignations of Urjit Patel and Viral Acharya, saying this was an indication of a huge disagreement between the RBI and Centre.

Another reason why this transfer is opposed is, should the government use the windfall to increase government expenditure, the lack of production coupled with an increase in demand could lead to short-term inflation, contradicting one of the two major objectives of the RBI, price stability.

Conclusion

The RBI, an institution par excellence, has been the centre of controversy many a time. Although the sea is calm now, this issue had to be revisited because of the economic slowdown that has struck our country, in the sense that the use of these funds in this crucial juncture is bound leave a long-lasting impact on the Indian Economy. The government is presently stuck between a rock and a hard place, and it has two options (using the amount to fund present expenditure is also an option, but the fact that it represents a complete wastage of an opportunity to bring out momentous structural reform doesn’t qualify it to be an alternative)- either recapitalize banks, or increase government expenditure, say in the form of funding infrastructure projects and put money in the hands of people. What the government does, of course, is yet to be seen.

-Siddharth Sampath

References

For more on this, refer “I do what I do” by Raghuram Rajan. The specific part mentioned here can be found in Page 36 of the book.

An insider’s view into this can be found in the former Governor of RBI Y.V Reddy’s autobiography “Advice and Dissent- My Life in Public Service”.

Comments