Effect of Founder exits on New Ventures

- Economics Association Hyderabad Campus

- Mar 28, 2021

- 4 min read

Founders are an essential part of any firm. They play a critical role in the setting up and subsequent evolution of the venture. Despite the importance of founders within these ventures, estimates suggest that one or more founders depart within the first few years in at least half of multi-founder firms. In this article, we see how founder exits affect firms' performance and the factors that determine the extent of such effects.

Founders contribute human, social and financial capital to a venture and founder exits deprive the firm of these critical resources. From this perspective, the exit of one or more founders disrupts the working process and leads to an adverse impact on performance.

On the other hand, some scholars contend that founder exits might be beneficial for a firm. If the departure of one (or more) members of the founding team facilitates more efficient and effective decision-making, an exit is potentially beneficial. As a new firm grows, it doesn't have the luxury of waiting for a consensus to evolve between multiple founders before making a decision because of the fleeting nature of opportunities, the dynamic nature of new venture environments, and the need for quick solutions to various problems. Accordingly, from this perspective, founder exits might be precisely what is needed for the venture to survive and thrive. Understanding and agreement may be better with the remaining founders, who then can reach decisions more quickly and decisively.

In sum, while exits deprive the firm of valuable resources, they might also improve coordination, communication and understanding among the remaining founders, especially early in a firm's life when the management processes haven't emerged yet.

To analyse the net effect of founder exits on a firm's performance, we can look at longitudinal datasets containing the information regarding performances of multi-founder firms with one or more occurrences of founder exits.

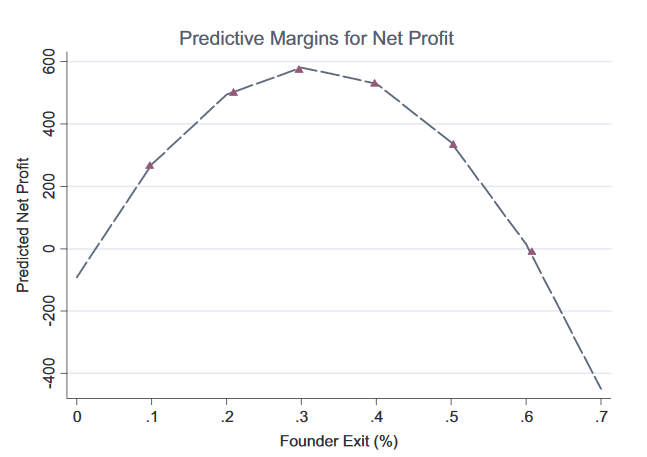

Through econometric analysis of such datasets, many studies have concluded that the relationship between the percentage of founders exiting in a multi-founder startup and its subsequent performance is curvilinear with an inverted-U shape. Firms having up to 60% of the founders' exit saw a general increase in performance. In contrast, the performance fell when a higher percentage of founders left. In one such study that included data for around three thousand ventures with at least one occurrence of founder exit, the inflection point was found to be at about 30%.

Apart from the general inverted U-shaped curve, many studies also found three main factors that decide the steepness of the curve or the magnitude of impact on the firm's performance:

Ownership concentration:

Founders in new firms often have differing control over the firm through various roles and responsibilities. The operations of a firm in which one or more founders own a large share of the firm differ from that of a firm with multiple founders holding smaller stakes. The difference is manifested in the way decisions are made and influenced within the firm. When ownership concentration is high, there is increased monitoring and better control over the firm. When ownership is distributed, control tends to be diffused, and monitoring is difficult. Though not necessarily most suited for the firm, high ownership concentration aligns the interests of the firm with those of the largest owners. It enhances the speed of decision making and resolving holdups. Therefore, the relationship between founder exit and firm performance is less salient (flatter curve) when there is high ownership concentration than when there is low ownership concentration.

Activeness of the founders:

Not all founders in a firm are active, irrespective of their ownership proportion. Though active involvement of the founders certainly benefits the team, passive founders provide the firm's access to the founder's resources without the encumbrance of needing a consensus on all decisions. They are less likely to influence the day-to-day operations of the firm. Therefore, passive ownership permits informal separation of ownership and control akin to established firms with a board of directors. Thus, the effects of founder exit on performance will be less salient in the presence of passive founders relative to active founders.

Ownership formalisation:

In terms of formalisation of ownership, some firms have a contractual delineation of ownership rights. It defines the scale and scope of the power vested with each individual founder and the division of responsibilities and hence facilitates coordination. Formalisation of ownership also reduces the amount of discretion a respective owner can have as privileges and responsibilities are clearly stated in the contract. Without such a formalisation or when the formalisation is weak, there may be ambiguity and uncertainty regarding the rights and authority of individual owners who will seek to define their own power. In contrast, when there is a strong formalisation of ownership, there will be fewer deadlocks in the decision-making processes, and management activities of the firm will be less complicated. Therefore, when ownership is formalised, the relationship between founder exit and performance will be less salient.

To sum things up, the relationship between founder exits and firm performance is non-linear and has an inverted-U shape. The exit of a few founders helps muti-founder firms as it becomes easier to make decisions. The positive effect is more pronounced when ownership concentration is less, activeness of founders is high and there is no or little ownership formalisation.

References:

Bhawe, N., Gupta, V. K., & Pollack, J. M. (2017). Founder exits and firm performance: An exploratory study. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 8, 114–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbvi.2017.09.001

DeTienne, D. R. (2010). Entrepreneurial exit as a critical component of the entrepreneurial process: Theoretical development. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(2), 203–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2008.05.004

Aldrich, H. E., & Yang, T. (2013). How do entrepreneurs know what to do? learning and organizing in new ventures. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 24(1), 59–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-013-0320-x

Pearce, C. L., Conger, J. A., & Locke, E. A. (2008). Shared leadership theory. The Leadership Quarterly, 19(5), 622–628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2008.07.005

Beckman, C. M., Burton, M. D., & O’Reilly, C. (2007). Early teams: The impact of team demography on VC financing and going public. Journal of Business Venturing, 22(2), 147–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2006.02.001

Wagner, W. G., Pfeffer, J., & O’Reilly, C. A., join(' ’. (1984). Organizational Demography and Turnover in Top-Management Group. Administrative Science Quarterly, 29(1), 74. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393081

Comments